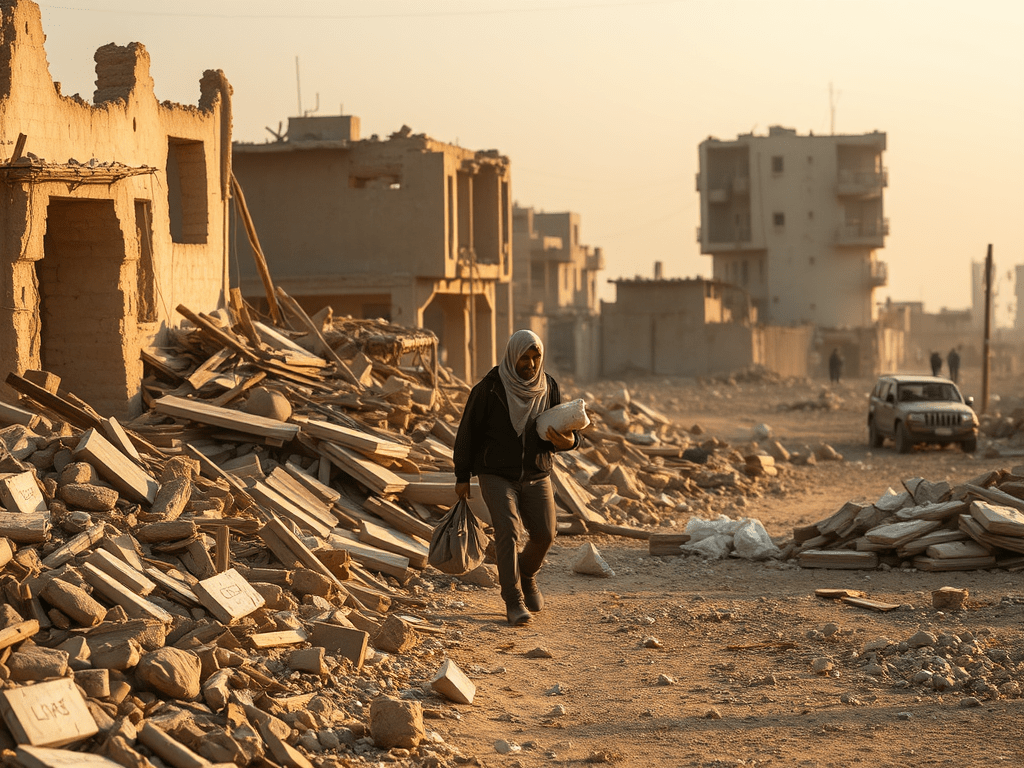

From the very first moments of the Syrian revolution, women were never mere spectators of events; they were an essential part of the revolution and a cornerstone of the Syrian people’s struggle. She is the mother of the martyr, his sister, his wife, and his daughter. Women paid a heavy price in tears and suffering, yet they remained steadfast and resilient, protecting their homes, raising their children, teaching in schools, and tending to the wounded in hospitals and field clinics.

Syrian women played multiple roles: the nurturing mother who bore the burdens of displacement and exile, the teacher who continued her mission despite bombardment, the doctor and nurse who stood beside the injured, and the fighter who took up arms to defend her homeland, offering her blood for the sake of freedom.

History has recorded unforgettable names of Syrian women who gave their lives for liberty, among them:

Martyr Suad Kiari, who fell while defending her land against the oppressive regime.

Martyr Joud, who fought until the very moment of her death. Just minutes before she was killed when her home was struck by regime missiles, she wrote on her Facebook page:

“O Allah, goodness in every choice, light in every darkness, ease in every hardship, and reality for all that we hope for. O Allah, by the beauty of Your paradise, show me the beauty of what is to come in my life, grant me what I wish, and expand my heart… O Allah, grant us contentment that makes our hearts peaceful, our worries fleeting, and our trials easy.”

Martyr Iman, a young teacher who was killed alongside her students under bombardment, symbolizing the sacrifices of Syria’s educators.

Martyr Samer, a Quran teacher who instilled faith in the hearts of her students before joining the ranks of the martyrs.

Alongside the martyrs stand heroic mothers who embody endurance and sacrifice. Among them is Um Ahmad, who lost five of her sons on the path to freedom, yet remained steadfast, holding her head high with pride, declaring that the blood of her children is a trust she carries, and that she will remain loyal to their cause until the revolution’s goals are fulfilled.

Syrian women were never just victims of harsh circumstances; they were partners in shaping history. Their patience under siege, their resilience in the face of bombardment, and their work across all fields made them symbols of the Syrian revolution and living examples of sacrifice and courage.

Thus, Syrian women have proven that they are not only half of society but also its driving force, its resisting voice, and its enduring spirit. The future of a free Syria cannot be complete without their active participation in all spheres of life.

المرأة السورية ودورها في ظل الثورة السورية

منذ اللحظة الأولى لانطلاق الثورة السورية، لم تكن المرأة مجرد متفرجة على الأحداث، بل كانت جزءًا أصيلًا من الثورة، وركنًا أساسيًا في نضال الشعب السوري. فهي أم الشهيد، وأخته، وزوجته، وابنته. وقد دفعت أثمانًا باهظة من دموعها ومعاناتها، لكنها بقيت شامخة وصامدة، تحفظ بيتها، وتربي أبناءها، وتدرّس طلابها في المدرسة، وتداوي جرحى الثورة في المستشفيات والعيادات الميدانية.

لقد لعبت المرأة السورية أدوارًا متعددة: فهي الأم المربية التي تحملت عبء النزوح والتهجير، والمعلمة التي واصلت رسالتها رغم القصف، والطبيبة والممرضة التي وقفت إلى جانب المصابين، إضافة إلى كونها المناضلة التي حملت السلاح في وجه المعتدين، وقدّمت دمها في سبيل وطنها الحر.

وسجّل التاريخ أسماء خالدة من النساء السوريات اللواتي قدّمن حياتهن فداءً للحرية، منهن:

الشهيدة سعاد كياري التي ارتقت وهي تدافع عن أرضها في وجه النظام البائد.

الشهيدة جود، التي ناضلت في حياتها حتى لحظة استشهادها، وقد كتبت على صفحتها على فيسبوك قبل وفاتها بدقائق بسبب قصف النظام البائد لمنزلها بقذائف صاروخية:

“اللهُم خيرًا في كلّ اختيار، ونورًا في كل عتمة وتيسيرًا لِكل عسير، وواقعًا لِكل ما نتمنى، اللهم بحجم جمال جنتك أرني جمال القادم فى حياتي وحقق لي ما أتمنى، واشرح لى صدري.. اللهم الرضا الذي يجعل قلوبنا هادئة وهمومنا عابرة ومصائبنا هيّنة”

الشهيدة إيمان، آنسة في مدرستها، التي استشهدت مع طلابها تحت القصف لتكون رمزًا لتضحيات الكوادر التعليمية في الثورة.

الشهيدة المعلمة سمر، مدرّسة القرآن، التي غرست قيم الإيمان في قلوب طلابها قبل أن تلتحق بركب الشهداء.

وإلى جانب الشهيدات، نجد قصص أمهات عظيمات قدّمن أعظم التضحيات، مثل أم أحمد التي فقدت خمسة من أبنائها على درب الحرية، لكنها بقيت صامدة، ترفع رأسها بكل شموخ، وتقول إن دماء أولادها أمانة في عنقها، وإنها ستبقى مخلصة لطريقهم حتى تتحقق أهداف الثورة.

إن المرأة السورية لم تكن مجرد ضحية للظروف القاسية، بل كانت شريكة في صناعة التاريخ. فصبرها وثباتها في وجه القصف والحصار، وعملها في مختلف الميادين، جعل منها رمزًا من رموز الثورة السورية، وعنوانًا للفداء والتضحية. وهكذا أثبتت أنها ليست فقط نصف المجتمع، بل هي قوته الدافعة، وصوته المقاوم، وروحه الصامدة، وأن مستقبل سوريا الجديدة لن يكتمل إلا بمشاركتها الفاعلة في كل مجالات الحياة.