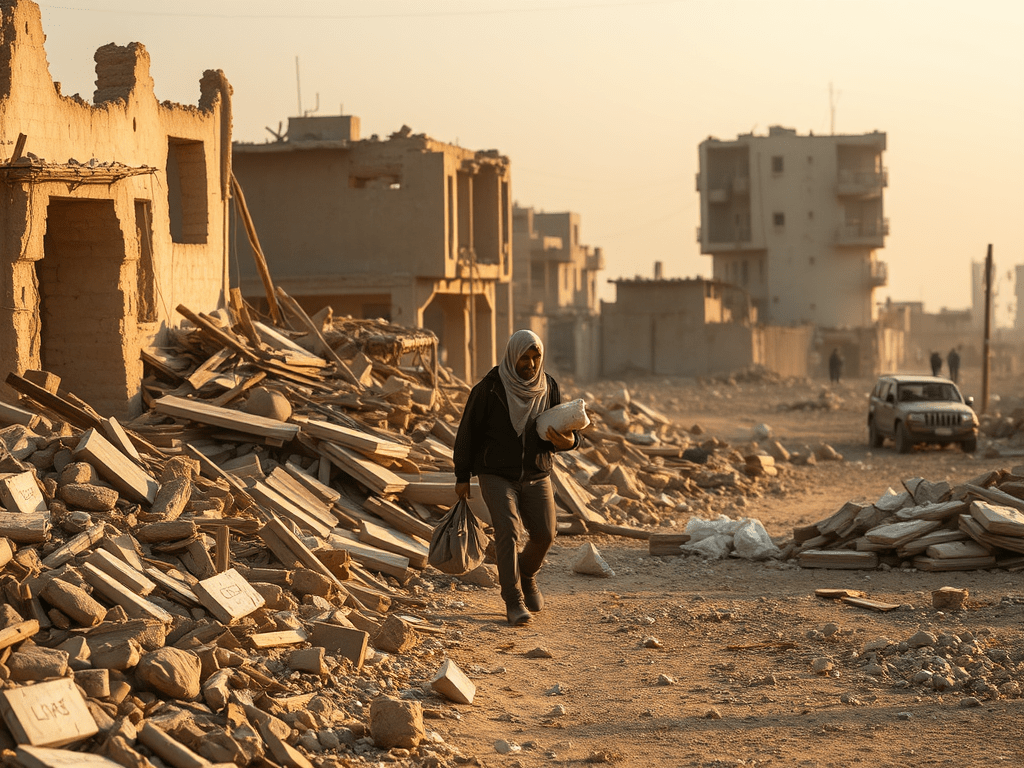

In the wake of Syria’s tumultuous political upheaval, a fragile hope flickers across a war-battered landscape. With the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 and the appointment of Ahmed al-Sharaa as interim president at the Syrian Revolution Victory Conference the following month, the country finds itself at a critical juncture. The civil war has left behind not just ruins, but deep societal fractures: ethnic, sectarian, and institutional, that threaten to undermine even the most promising reforms.

Among those navigating this uncertain future are humanitarian organizations that have been working in Syria for years, often in the shadows of violence, bureaucracy, and mistrust. Their perspectives offer a sobering look at the country’s path forward and the many obstacles that still lie ahead.

A Promise of Reform, Weighted by Reality

Perhaps the most unlikely figure to emerge as a transitional power broker is former HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa. His recent rebranding, marked by public commitments to hold elections, uphold civil liberties, and guarantee religious freedom, has raised both hope and skepticism.

While his rhetoric signals a break from the past, the reality remains complex. There is a visible desire to stabilize and present an image of order, but the foundations for governance remain weak. Institutions are broken. Ideology continues to influence decisions related to aid distribution, urban recovery, and civic life.

This challenge is compounded by a fragmented, hyper-localized landscape. Despite a change in leadership, interference, favoritism, and ideological pressure continue to obstruct humanitarian delivery. This can take the form of demands to prioritize aid for politically favored groups or pressure to conform to socially conservative norms.

Bureaucracy, Banking, and Bread

Across Syria, operational challenges are severe. Organizations must navigate a convoluted approval process involving umbrella organizations like the Syrian Development Organization (SDO), the Humanitarian Affairs Committee (HAC), and local authorities.

The process is sometimes more negotiable than under the previous regime, but liquidity constraints and exchange rate instability undermine project planning. Aid groups frequently see budgets devalued due to delays and currency fluctuations.

Access restrictions persist in areas like Dara’a and As-Sweida, and banking challenges paralyze operations. Delays in payments and procurement have been challenging.

Meanwhile, urgent humanitarian needs remain. In Jizraya, NGOs are running bakeries to ensure food security. In Kwaires, farming communities are supported with seeds and inputs to restart agricultural production.

However, these initiatives remain fragile, vulnerable to renewed violence, shifting political winds, and fluctuating donor support.

Safety by Silence

Security remains tenuous, shaped by a patchwork of actors. The formal police are undertrained and lack legitimacy. Local militias and armed factions often assert authority where government institutions are weak.

In rural Deir ez-Zor, concerns persist about the presence of foreign fighters and sporadic Daesh activity. In other areas, low-intensity conflict and factional violence remain unresolved.

In this context, many humanitarian actors avoid confrontation and self-censor to preserve access. Navigating complex ideological environments requires discretion and compromise, particularly in areas where conservative religious or political pressures shape public life.

Ideological backlash has disrupted aid projects. Initiatives seen as overly secular or Western have faced public campaigns and online harassment. Religious infrastructure projects, often backed by external donors, possibly Gulf states, are expanding rapidly, sometimes at the expense of cultural and civic spaces.

Ethnic Fractures and Fragile Coexistence

Ethnic and sectarian tensions remain deeply rooted. In urban centers like Damascus and Aleppo, coexistence is often pragmatic, driven by shared economic needs. In rural and coastal areas, where communities are more homogeneous, mistrust and historical grievances persist.

Aid distribution, housing, and education are often viewed through the lens of identity. Neutrality is difficult to uphold when resources are scarce and every decision is politically sensitive. Even well-intentioned humanitarian efforts risk becoming entangled in local power dynamics.

Looking Ahead: Building or Breaking?

Despite the challenges, there are reasons for cautious optimism. Efforts to revitalize agriculture, reintegrate former combatants, and restore cultural landmarks may offer a foundation for long-term resilience. These interventions, if protected and supported, could help rebuild livelihoods and social cohesion.

But this path forward requires more than technical expertise. It demands trust, reconciliation, and local empowerment—none of which are guaranteed in today’s Syria. Leaders like Ahmed al-Sharaa may speak of a new era based on pluralism and civil liberties, but the conditions on the ground remain fragile.

The real work of recovery is taking place quietly, far from official statements and televised announcements. It is found in engineers restoring roads, women planting gardens, teachers reopening schools, and aid workers navigating impossible choices to serve their communities.

This is where Syria’s future will be decided: not in headlines, but in the day-to-day struggle to rebuild a country that has lost so much, yet still holds the possibility of renewal.